Six Book Club Members have volunteered to help lead the Tarantula discussion (many thanks!). Jeff Harrison teaches a Dylan course in the English department at Lane Community College in Eugene and plays Dylan a lot on the radio, in a weekly program he hosts called "Deadish" and, like many folks, his first show was in the early '74 tour; he caught the Charlotte concert. Jeff will lead off our discussion based on a short essay he developed as a context for Tarantula. Timothy Drake writes that his father was a major Dylan fan and this exposure began his association with Dylan’s music—Timothy has taught Dylan’s songs in university English courses for close to 20 years. Jeff Passe is a writer living in Seattle and is working on a novel about a bunch of Dylan fans. Daniel A. Singer, the Cantor at the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in Manhattan, has built a reputation as one of the most renowned Reform cantors in the United States. He grew up immersed in the folk music scene of Duluth-Superior and is an accomplished recording artist, multi-faceted guitarist, pianist and composer of new music for the synagogue and stage. Mary Connell is a retired clinical and forensic psychologist in Fort Worth, Texas, and finds pleasure in tending to her shade garden and in all things Dylan. Peter White (see his essay on Why Tarantula is Hard to Read), a co-founder of the Book Club, is a retired professor of ecology in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, plays lots of music, and has been connected to Dylan since the age of 14.

What Is Tarantula?

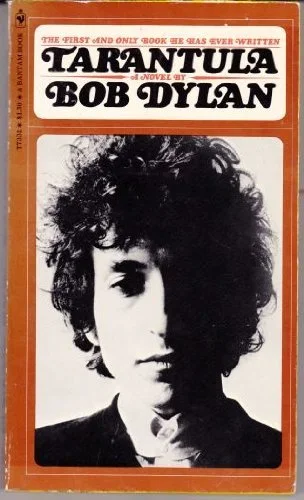

Well, for one thing, it “defies easy classification”. The cover of the original paperback calls it a “novel”. Given its length (just 149 pages), some refer to the book as a “novella”. It has also been called a collection of free verse or prose poems. Sarah Hillenbrant Varela quotes Gabrielle Goodchild who called Tarantula a “book-length series of free association passages”.

Dylan developed an interest in writing prose poems in the early 1960s (see Book-Of-The-Month notes for March 2024). This approach to poetry may have been attractive to Dylan precisely because it dispensed with the constraints of the song form at a time when he needed “a dump truck, mama, to unload my head” because he had “a headful of ideas that are drivin’ me insane” and “every thought that strung a knot I my mind, I might go insane if it couldn’t be sprung”. In form and content, Tarantula is clearly related to the liner notes for Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited, which were written in the same time frame as Tarantula. In turn, these liner notes can been seen as having evolved from Dylan’s earlier interest in writing free verse poems for his own albums or those of other artists, as well as poems presented in other settings, such as the program booklet of the Newport Folk Festival and “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie”, read aloud at his Town Hall concert on April 12, 1963.

Tarantula has no chapters but there are 47 parts or sections with bolded titles like the "Guns, the Falcon's Mouthbook & Gasheat Unpunished", "On Busting the Sound Barrier", “Hopeless & Maria Nowhere”, and “Note to the Errand Boy as a Young Army Deserter”. Some of these sections are just one page, others more than 10 pages long. Often the sections contain letters that begin or end with such phrases as “dear dropout magazine”, “whatcha doin’?”, "say hi to your doctor, love, Toby Celery", "your friend, homer the slut", and "your crippled lover, benjamin turtle". As these lines suggest, Tarantula is very funny, even hillarious, at times, though, as John Bauldie wrote, it is also “grimly serious”. Bauldie asks, what are we laughing at? The usual target: the “folly of mankind”.

Many characters appear in Tarantula, often just once, but a few (for example, Aretha and Maria) appear and disappear throughout.

Dylan alludes to his own work throughout Tarantula. To take one example, there is a section called “Ballad in Plain Be Flat” that obviously references the 1964 song “Ballad in Plain D”—but here the key is changed from D to B Flat, which has morphed into “Be Flat” and thus becomes a pun that might conjure up Hamlet’s “to be or not to be”. But what does “be flat” signify? Horizontal in the grave? Defeated, generally? Laying Low, trying to hide or blend in? Or does it signify “to be out of tune or out of step”? By quoting and modifying his own songs Dylan communicates the message that a song has a cloud of possible meanings within which the meaning is perhaps trapped, if never directly stated. Tarantula participates in that effort. As Dylan fans know, he persisted in his allusion to his own work and in rewriting his own lyrics.

Tarantula’s Reception

In a 2020 essay, Sarah Hillenbrant Varela presented a summary of Tarantula’s reception (while also presenting an interesting argument of its relevance to Rough and Rowdy Ways). Tarantula has been called “overlooked”, “forgotten”, “neglected”, “obscure”, “baffling”, and “experimental”. One reviewer started his essay with “charmingly ridiculous is the nicest thing anyone could say”. Varela included the note that Dylan was 23 when it was written, so that some have considered Tarantula “failed juvenilia”. Varela also cites Margo Price’s description of Tarantula as vomit, a description that likely comes from Dylan himself—he has commented that Like a Rolling Stone began as 20 pages of vomit.

Some have used the phrase “stream of consciousness” for Tarantula but, to me, this seems a bit off because one can sense a purposeful structure and recurrent themes that drive the book forward.

In any case, Dylan himself seemed to have moved passed Tarantula by the time it was published (about 5 years after it was deemed ready for publication), which may be partly why it wasn’t fully discussed or promoted by Dylan himself.

Tarantula’s Title and Meanings

Dylan has not explained the title. Here are my observations (many inspired by Witting’s 2023 book help those that cannot understand not to understand: A Guide to Reading Tarantula): A tarantula is a solitary creature with a sharp sting. It’s appearance is frightening. It is ready and armed. Danger and threat walk the line between aggressive and defensive behavior. The tarantula is posed to strike, but there is uncertainty as to whether it will strike or not. Is it, sometimes, just a defensive bluff?

Whether Dylan was thinking of those ideas or not, the title “tarantula” does seem to represent what Dylan writes about in Tarantula: he describes a world of latent violence and conflict. The world is corrupt, facilitated by propaganda, gullibility, and brainwashing that create blind acceptance of social/cultural norms. John Bauldie wrote that Tarantula describes an urban American wasteland, in which there is a constant struggle for power, with violence is never far from the surface, and where “money [is] a major root of social evil”. Authoritarian societies demand and police conformity. As a result “it is everyman for himself” in a struggle that is factitious and chaotic. It is possible that the tarantula is found in all parties in these conflicts. It is also possible that artists and Dylan himself are represented by the tarantula, already in a defensive position and ready to strike at social corruption that is described above. More generally, though, it seems that the role of the artist is to hold up a mirror, so that we can discern “what is true and what is not”. This is also a key to dodging the selfish “games people play” in trying to accumulate wealth and power. One way of looking at Tarantula is that it is a warning. It can’t be all bleak. Dylan also sang “there must be somewhere out of here”. In mid-1960s interviews he claimed that all his songs end with “Good luck. I hope you make it through” and, in one song contemporaneous with Tarantula, he sang “I’m pledging my time to you, hopin’ you come through, too”. 56 years later he gave the advice “Stay safe, stay observant, and may God be with you”.

A Whirlwind of Change, 1964-1966: Song structures, themes (philosophical questions explored), public attention (interviewers), global fame, fashion, and a developing family life

Tarantula emerged at a time when Dylan’s world was rapidly changing. It was a period of great experimentation, growth, and excitement, including going electric, a global tour, getting booed, as well as cheered, and becoming seriously burned out. Though rooted in folk, country, rockabilly, and blues, Dylan was revolutionizing the themes, structure and instrumentation of his songs, including the shift to electric guitar, bass, keyboards, and drums—and greatly influencing all of popular music in so doing. Other artists were enthusiastically covering his songs. He acquired sunglasses, silk shirts, and leather jackets.

The change in the questions Dylan was exploring is especially notable for Tarantula. In My Back Pages (1964) Dylan had announced that his earlier songs had addressed social protest through the lens of someone who knew how to define the issues: “good and bad I defined these terms, quite clear, no doubt, somehow” and he “spouted out that liberty was just equality in school”. Now he saw beneath the surfaces of those questions. Now he was younger and more open, not yet secure in his understanding of the complexities of the relation of individuals to social structures. In December 1963 he was given the Tom Paine Award by the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee for “distinguished service in the fight for civil liberties” and, in his comments from the podium, he said that “it had taken him a long time to get young and now I consider myself young…I’m proud that I’m young”, that is to be open to new questions and perspectives. He is suspicious of blind acceptance of and conformity to society’s expectations and constrasts that with individual freedom, e.g., in songs like Subterranean Homesick Blues and Like A Rolling Stone. In our April 2025 Book-of-the-Month Jeffrey Edward Green articulated in detail Dylan’s career-long conflict between individual freedom and community justice as a key to understanding his work.

In 1963-1964, Dylan had been saying in interviews that he was going to branch out, maybe into play writing or movies, or maybe books. Between the lines, one got the feeling that he had begun to feel that the song form was limited. There were rumors that he had, in fact, begun writing a book. However, he seems to have stopped working on the book mid-1966 (he may have carried the publisher’s proofs for corrections on his 1966 tour). Thereafter, the project lay dormant—until Dylan finally (and, as far as I know, without explanation) withdrew his objection to publication in 1971 and so Tarantula was finally released by the Macmillon Company (Dylan’s copywright for the published work was dated 1966). In the 5-6 years since Dylan stopped working on the book, several versions were circulating as bootlegs. The publisher’s preface for the book, entitled Here Lies Tarantula, gives a brief history (linked HERE).

In 1964 and 1965, other changes were afoot that help explain Dylan’s on-again, off-again work on Tarantula. Dylan, the “quickly famous shy boy” as he was called in Tarantula’s preface, had in fact discovered that he could greatly expand in song form and the complexity of themes he was writing about, starting with Bringing It All Back Home (released March 22, 1965), followed just five months later by Highway 61 Revisited (August 30, 1965) and a year after that by Blonde on Blonde (June 29, 1966). The artistic and financial success of these albums lessened Dylan’s desire to develop other writing projects. In a 1966 interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation he had said "After writing that [Like A Rolling Stone] I wasn't interested in writing a novel, or a play... I wanted to write songs... I mean, nobody's ever really written songs [like that] before".

On July 29, 1966, Dylan was injured in a motorcycle accident near his home in Woodstock, New York. In Chronicles he wrote “I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” After the accident, he withdrew from performing and public appearances, though he was still writing and recording.

Starting in 1994, Robin Witting has written five essays on Tarantula, but notes that the last of these, an e-Book entitled help those that cannot understand not to understand: A Guide to Reading Tarantula (2023), “crystalizes and clarifies and exemplifies all my thoughts on Trantula…[and] is the sum-total of all those years' toiling to grasp” [Tarantula] (personal communication to Peter White, September 2025). This e-book is a must-read for Dylan fans wishing to go deeper on Tarantula and the download is inexpensive!

From an interview with Christopher Ricks in The Dylan Review Vol. 1.2, Winter 2019 (linked HERE):

Ricks: “Tarantula is evidence of things about Dylan. It’s less good than the songs for lots of reasons. But the letters in it are terrifically good. Everything about the butter sculptor, everything about the professor who says, “Don’t forget to bring your eraser.” All those things are very good. Anyway a lot of it is evidence. ‘April or so is a cruel month,’ is not quite the very the best thing that Dylan ever does with Eliot, but It’s a lovely thing to have done with Eliot—even if it’s not as good, as deep, as ‘Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot fighting in the captain’s tower.’ The great thing is the depth with which Eliot is apprehended. ‘April or so is a cruel month’ is witty—I wish I had thought of it myself”.

Witting (2023) quoted a 1966 London Press Conference:

Press: Tell us about the book you’ve just completed!

Dylan: It’s about spiders, called Tarantula. It’s an insect book. Took about a week to write, off and on … my next book is a collection of epitaphs.

Witting speculates that the title Tarantula is an allusion to Nietzsche’s Of the Tarantula from Also Thus Sprach Zarathrusta and possibly also “the spooky 1955 sci-fi movie Tarantula”. Nietzche’s tarantula is a venomous creature out for revenge.

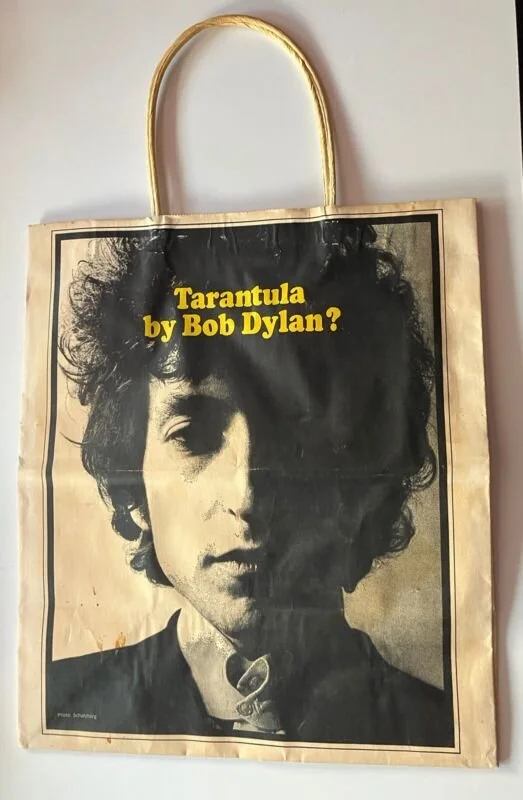

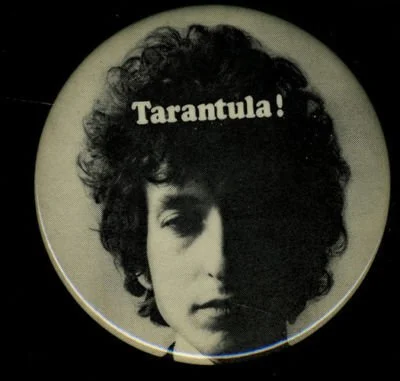

Promotional pieces developed for Tarantula in 1966 before the long delay to a 1971 publication

Links for fun!

Is Tarantula a representation of Dylan’s natural gift for rhymes, rhythms, and word play, and his “headfull of ideas”? Do we ever see this Dylan trait in live action and real time? How about this: Bathe My Bird!

Can we hear songs in Tarantula? With Stumpzian we go 180 degrees from this question and ask, Can we hear everyday conversation in Dylan’s songs?

Try a few of these:

She’s Your Lover Now, I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine, The Wicked Messenger, Leopardskin Pillbox Hat, On the Road Again, I and I, Positively 4th Street

—Peter White, October 2025

Dylan wrote in his Nobel Prize Speech that his songs were “meant to be sung, not read on a page”. Tarantula has a rhythm which can come to life when it is read aloud—on the audio version, released by Simon & Schuster Audio in 2019, Tarantula is read by actor Will Patton.

BREAKING NEWS: Robin Witting was invited to write the introduction for a Chinese translation of Tarantula! Robin writes that it was “a beautiful hardback edition albeit in Mandarin”. 10,000 copies were printed. READ WITTING’s introduction HERE! And for of a celebration of balladry and Tarantula by Witting, click HERE.

Other Tarantula links to explore!

Robin Witting’s introduction to the Chinese edition HERE!

John Bauldie’s The Chameleon Poet, our July 2025 book-of-the-month, was one inspiration for our October focus on Tarantula. Some excerpts from Bauldie’s book that discuss Tarantula are linked HERE.

Robert Christgau’s review of Tarantula in the New York Times (linked HERE).

A review of Tarantula by Ewan Gleadow (linked HERE)

An 2020 article by Sarah Hillenbrand Varela, Revisiting Bob Dylan’s Tarantula in a Rough and Rowdy Time (Inter]sections 23:79-91, linked HERE)

Remarks by the man who translated Tarantula into Polish: A Happy Tarantula Reader by Filip Łobodziński, posted on Untold Dylan by Tony Atwood (linked HERE)

Excerpts from an August 1965 interview of Dylan by Nora Ephron and Susan Edmiston (HERE). Like the KQED Press Conference (below), this interview gives us a view of Bob Dylan’s interests and purposes as Tarantula was being written and edited.

KQED San Francisco Press Conference, December 1965, during which Dylan is asked what his (unnamed) book is about. Dylan answers “It’s about just all kinds of different things—rats, balloons” (linked HERE)

Another late-breaking post: Ron Rosenbaum gave a lecture at Stanford that was inspired by eight words of a poem in Tarantula: "hitler did not change history, hitler WAS history". Rosenbaum’s article on his talk is posted HERE, along with links to the text of the entire poem HERE, and an article by Sean Curnyn reacting to those words and Rosenbaum's take HERE. Thanks to Book Club member Ellen Kessler for bringing this to our attention.

Why is Tarantula so hard to read? Peter White’s draft essay is HERE—send him comments.

Sample of bootleg editions of Tarantula